In many ways, it’s the timetable equivalent of First Great Western having to cram as many airline seats as possible into its HSTs to satisfy government’s demands for commuters east of Didcot. That the same trains must also serve West Country holiday traffic, with families who would like to be around a table of four, is lost in the capacity argument.

Another downside of clockface services is that they can tie several routes together, making changes in one hard to implement without ripples affecting another. The difficulty of those changes becomes much harder as lines become more congested, which partially defeats the reason for clockface in the first place. Pity the timetabler trying to put the last line into a clockface - what works at one end of a line might be completely out-of-sync at the other.

A busy clockface timetable also demands a reliable railway, both track and trains. In this regard, the ECML does not have a good record. For many years, it’s been on or around the bottom of the performance league table, although recent performance has been improving.

Adding more trains generally results in yet poorer performance. That’s certainly the picture that has emerged following the addition of a fifth trans-Pennine path in May 2014 - NR found that right-time performance fell by a thumping 17%.

The massive reorganisation of West Coast Main Line services associated with Virgin’s very high frequency timetable in 2008 led to a 15% fall in right-time running. An exception can be found on the ECML, where May 2011’s Eureka timetable resulted in a 1.5% increase.

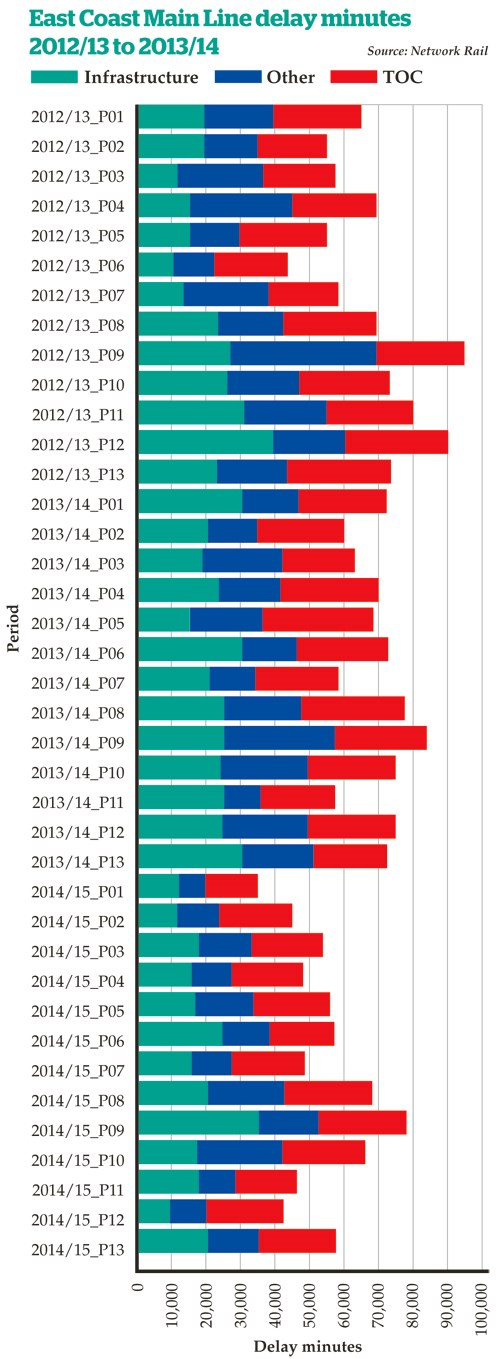

Network Rail collects a vast amount of performance information for the route, classifying delays according to their cause. Some cause particular peaks - overhead line equipment tends to cause major delays when it collapses (up to 9,000 minutes in some periods), but this doesn’t often happen. In contrast, technical fleet (train) faults have caused at least 8,500 minutes in all but a couple of periods over the past two years.

Both are on declining trends, contributing to the overall increase in punctuality across the route. Both points and track circuit failures are also falling. On the other hand, signal failures are rising (an average of 1,000 minutes delay per period over the last year).

One rising trend that is expected to continue is that of passenger numbers, which have already doubled since privatisation. With Britain’s population expected to keep growing, rail numbers should keep increasing, even if the sector fails to win any increase in market share from air and roads.

In 2009, NR reckoned the increase over 2007-2036 would be between 34% and 78%, depending on the direction the country moved. Updated work in 2013 put the 2012-2023 rise between London and Leeds at 14%-48%, to Newcastle 12%-58%, and Edinburgh 14%-43%.

The response to these predictions has been to provide more rail capacity, hence the CP4 and CP5 programmes. Yet for the provision of roads this ‘predict and provide’ model has been discredited after many years of faithful application by governments, because it simply responded to demand rather than trying to shape it for the country’s benefit.

Predict and provide can be justified if its application makes Britain a better place (not the easiest thing to measure). Taking rail as a greener transport option than road or air, providing more rail capacity in order to make UK transport greener overall could be a valid policy.

The increase in passenger numbers since privatisation has been coupled with an increase in rail’s market share since then, from a low of around 5% to nearer 8% today, perhaps justifying predict and provide.

However, in its 2012 High Level Output Specification for 2014-2019, the Department for Transport makes no mention of increasing modal share. There is no mission to cut short-haul air with fast journeys of the sort proposed by Alliance and FirstGroup. Instead, it calls on the rail industry to deliver “dynamic, sustainable transport that drives economic growth and competitiveness” while reducing costs by £3.5bn, to make it “more financially sustainable and lessening the burden on farepayers and taxpayers”.

It does specify an increase in capacity for freight and franchised passenger services. It also directs that up to £240m be spent to improve the East Coast Main Line.

That’s very close to unjustified predict and provide.