Getting the right mix of investments requires the ability to set priorities and the ability to fulfil them. UK cities currently have little leverage in this, because of the centralised nature of decision-making in this country.

This has been extensively investigated in recent years, by the City Finance Commission and the London Finance Commission, as well as by the Government. The most recent publication was by the City Growth Commission, of which I was a commissioner.

Once again, it has highlighted how the UK is the most centralised of developed economies and how even recent City Deals and Growth Deals have had only very limited impacts on this. They propose that city regions - metros - should have the ability to access greater independence in finance and investment, subject to some selection criteria to show that the city has the requisite skills and tax base.

Appraisal and funding system

A consequence of the UK’s centralised system is that funding for cities comes down a complex set of pipes, with no connections or integration at the city level. A more devolved system could not only take a more coherent view of the investment needs of a city, it could also prioritise on a wider set of criteria than is currently possible. In particular, such criteria can be focused on economic potential and growth as much as on welfare (or user benefits), which is the basis for current spending decision-making in government departments such as the Department for Transport.

The UK’s current appraisal and funding system is based on the assumption that transport investments are made to generate welfare improvements for passengers, rather than to change the economy’s output potential. Where change is only incremental, it may well be reasonable to consider the economy as being independent of transport in this way. However, where there is the potential for structural economic change, accompanied by major spatial change locally and regionally, this is unlikely to provide a sufficiently full view of likely future transport requirements.

Our appraisal system insists on using models in which the past informs assumptions about the future, but the changes experienced at Canary Wharf show that past trends are not, in all circumstances, a useful guide.

This is a very important realisation - it suggests that our current static framework for evaluation, particularly of large-scale and long-term projects, is inappropriate. It will not capture the feedbacks that change the nature of places, even when so-called ‘wider benefits’ are taken into account.

What should be asked is: what constraints exist, how serious are they, and what might relieve them? The further question is to gauge the extent of new opportunities - how they can be accessed, and what investment would make it possible to achieve them.

Localities can recognise and leverage the combinations of factors that create a place and attract variety of investment.

When first opened, Manchester Metrolink beat expectations of ridership and leveraged private investment into Manchester. Reinvestment in St Peter’s Square and in the airport has also resulted from better connectivity secured through the current Metrolink expansion programme. This expansion has been facilitated by a locally-led, risk-based funding programme with a significant proportion of finance secured through borrowings against future farebox returns and local council tax receipts.

Greater Manchester has thus been able to deliver regeneration-led investment projects (such as the Manchester Airport Metrolink extension) that would have performed less favourably under national welfare-based analysis approaches than under the productivity-led analysis and prioritisation used by the Greater Manchester authorities.

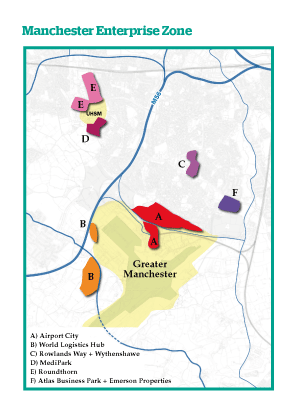

Argent, which led the redevelopment of the land between King’s Cross and St Pancras in London, is now leading the Airport City North development in Manchester - this forms a major component of the Enterprise Zone (see map, right) that has been identified around the only UK airport outside Heathrow with two runways.

Unless we make changes to our evaluation system, the UK will continue to miss out on the potential of its cities. Visionary schemes such as Crossrail, HS2 and the One North proposals rest precisely on their ability to be game-changers for city regions and the whole country. And they require complementary plans to be put in place to allow this to happen.

Strong risk analysis

What we need is a reformed system that looks both at returns on investment and allows these corresponding policies to be put in place. Major investment decisions must be shaped by a more holistic view of cities’ needs - it must start with the growth imperative and then be supported by strong risk analysis, rather than a narrow transport appraisal system that assumes the development of the economy is broadly independent of the transport system.

The proposition is actually fairly simple. Devolution and better transport and land use planning go hand in hand. Both for London and other cities, an integration of land use planning and development with the transport investment is central to economic growth and to future welfare. (Welfare has a particular meaning in economic theory that is narrower than its meaning in normal language.)

Maximising economic potential will require both inter-city and intra-city investments as well as parallel engagement from all cities, from London as well as outside it. Most importantly, the decision process needs to be reconsidered to focus on how payback is to be generated and by whom, so that financing and funding decisions can be aligned.

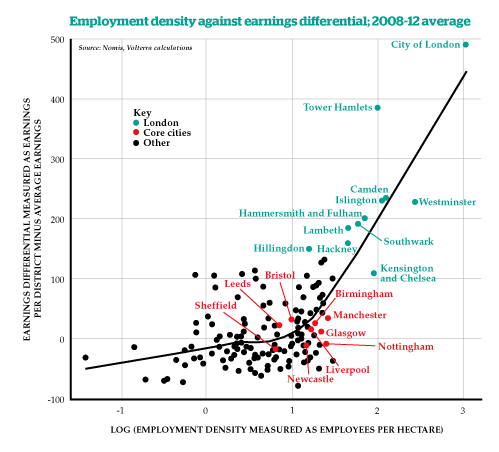

Maximising economic potential will require the building of dense city centres that can accommodate productive workers in knowledge-intensive firms and sectors. Such firms exist across a whole range of activities - from bio-medical research to 3D printing, as well as accounting and law. But creating dense city centres requires both commuter networks and external networks to access major markets, as well as the planning policies to support development.

A key conclusion is that creating a larger and more effective commuting potential for all the cities outside London should be a priority, as this has been neglected. And given the difference in scale, this suggests that more effective integration of these cities is required. Indeed, this is a key conclusion of One North: A Proposition for an Interconnected North, the One North report prepared in July 2014 by the cities of Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle and Sheffield.

The report concludes: “Our proposition builds on this common perspective and aims to create a North of England that is a powerful and integrated series of economic geographies. This will be a highly interconnected region of thriving cities and towns, providing a valuable counterweight and complement to London and helping to re-balance and deliver growth for the national economy in the decades ahead.”

Links between cities in the North are not as effective as those into London. The fastest link is between London Euston and Milton Keynes, with a journey time of 30 minutes for 50 miles. The distances between Sheffield, Manchester and Leeds are all shorter, with 39 miles between Sheffield and Leeds and between Sheffield and Manchester, and 43 miles between Manchester and Leeds. Yet the quickest trip is between Sheffield and Leeds (40 minutes), while Manchester to either Sheffield or Leeds is nearly an hour! There are also just ten trains between these three pairs of cities in the peak hour (0800-0900), compared with 11 just between Milton Keynes and London.

Devolution will be required to ensure that these elements can be effectively brought together, as well as to prioritise the investments that support growth in a manner that can be responsive to local economic conditions.

A process that focuses more centrally on the economy, through economic entities/geographies and corridors, will prioritise both revenues and output potential, as well as take a risk-reward perspective to investment rather than assume that the future will be like the past.

But a different approach requires an understanding of the mechanisms by which transport can be associated with economic performance. This was explored in High Speed Rail, Transport Investment, and Economic Impact, a 2013 paper for HS2.

It is not enough to observe that trip growth has been associated with economic performance, since correlation is notoriously not causation. Moreover, there is an increasing view that the performance of some cities has already been constrained by a lack of infrastructure of the right type. A focus on growth creation and the role of transport investment challenges our existing system of evaluation and how we think about finance and funding.

So what is to be done?

The focus of evaluation needs to concentrate on revenue and on the wider economic returns generated by major transport investment programmes. Instead of thinking about welfare benefits that do not exist in real money, we should concentrate on those that have direct value. It then follows that we should think about what revenue will not cover, and why there might be a case for such investment. This is where GVA, productivity impacts and returns to the national economy over time come in.