It’s said that there are two versions of events, and in the middle - the truth.

That could apply to the East Coast Main Line, which has been at the centre of conflict over the past few months as opinions swirl on how much room it has for growth (not much), its need for continued renewals investment on top of the £3 billion the Department for Transport has pumped into it already. and its current capacity concerns.

You can add to that the ongoing debate about its current operations - and specifically its operators.

One of those is of course LNER. The government-owned operator has just released a report claiming that over the next decade, its revenue will be £1.1bn lower as a result of competition with open access operations.

It also contends that open access operators (OAOs) have taken £628.2 million from some of the major stations on the line - the likes of Grantham, Retford, Doncaster, York, Newcastle, Morpeth and Edinburgh - between 2006 and 2025.

That would be a bitter pill to swallow for the DfT. It has long encountered problems on the line, including a timetable for which stakeholders from across the industry are currently trying to fit at least a couple of hundred more paths into an already crammed schedule.

Away from the headline numbers seen in the report, it’s important to delve a little deeper into how the report’s authors - consultant Jacobs - have arrived at their conclusions.

The report starts by acknowledging what the world would look like without open access operators existing at all.

It assumes that LNER’s service would be the same. This is a sensible approach, although unlikely given that there would likely be an improved service and with more elasticity of pathing available.

This assumption automatically means that stations where OAO services currently call would have a reduced service. According to the report, this would mean that a number of passengers wouldn’t travel, which it believes would lead to further revenue loss. It then assumes that the remaining passengers would travel by LNER using ‘LNER only’ tickets.

During the whole report, it measures time using the Generalised Journey Time (GJT) methodology.

As a metric in these types of situations, the GJT is common practice. In essence, it considers not just the time spent on the train, but also factors such as the frequency of service and the number of transfers needed. This, it is argued, gives a better measure of the service quality than just the advertised journey time.

To measure the impact of a change in the perceived travel time of a trip, an ‘elasticity score’ is given. In basic terms, this measures the flux between the GJT change and the drop in demand that results.

For example, a study might find that GJT elasticity for rail travel is -0.8. This means that if the average GJT of a particular rail route increases by 1%, the demand for that route would be expected to decrease by 0.8% - assuming all other factors remain constant.

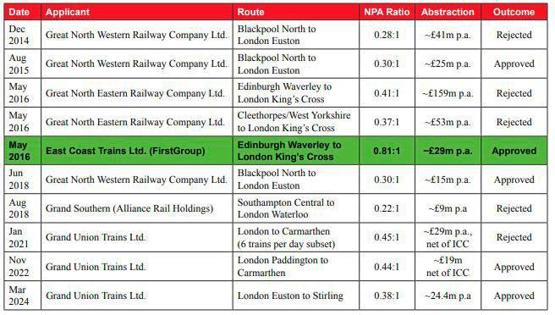

Graph caption: As highlighted in the table above, for every £1 abstracted, Lumo was expected to generate 81p. The Not Primarily Abstractive (NPA) test is one of the key tests in deciding whether or not an open access application is successful. Not many have passed since 2014. Source: Office of Rail and Road.

Based on the report, LNER’s biggest rival is Lumo. It says that prior to the commencement of Lumo operations (2021), “abstracted LNER revenue did not exceed £40m per annum. However, since then the detrimental impact of Lumo services on the LNER revenue stream is very evident”.

It adds that LNER’s estimated losses had risen significantly to £65m in 2023 and then £87m in 2025, although this is less of a slam-dunk than perhaps the report would like you to think.

Lumo runs directly against LNER in almost all its current services, so the likelihood that it abstracts more than other open access operators is greater. It was, after all, set up after winning a tender to take the remaining paths to those destinations that were not being used.

But it also launched during the COVID pandemic, which meant it faced significantly reduced revenue and cancelled services.

So, 2022 is a better starting point. On this basis, the revenue abstraction that the report refers to is likely a better reflection of where things stand regarding Lumo.

But also, LNER is generating more revenue than it was between 2015 and 2021. In 2015, in the markets that Jacobs measured in this report, revenue was £106m. In 2025, revenue was £251m. The share of OAO revenue that LNER would have earned without the existence of OAOs changed only marginally changed in that time period.

While higher than the DfT initially thought, there were warnings that a significant amount of revenue would be abstracted from franchise operators (as they were called) when the access was granted to FirstGroup (Lumo’s parent company) in 2016.

In a 2015 Office of Rail and Road (ORR)-commissioned report into the possible impact of multiple open access applications for the ECML paths (including Virgin Trains East Coast and Alliance Rail), it was estimated that total annual abstracted revenue would be £9.2m from FirstGroup alone.

This is in stark comparison to VTEC’s estimated abstraction at the time for the paths for which it gained approval (Middlesbrough, Edinburgh, Lincoln and Harrogate), which stood at £2.8m.

But the recommendations - and ultimately the purpose of the access approvals detailed in that report - were less to do with abstraction and more about the economic benefits and offering a competitive market against a backdrop of rising passenger dissatisfaction at high ticket prices and few competitive options.

That backdrop has altered little today, with all the current open access operators currently operating on the ECML - Grand Central and Hull Trains, as well as Lumo - releasing reports demonstrating that they believe the focus of the argument should be more towards choice.

FirstGroup has consistently argued that both Lumo and Hull Trains have driven service level growth on the routes where they operate.

In the example of Hull Trains, it has added direct services between Hull and London since it began operations in 1999, adding seven weekday direct services compared with none by the publicly-owned LNER. This in itself has meant more seats have become available, giving choice to passengers in a city with a population of 268,000.

As for Lumo, away from the major population centres, it has added five extra direct services per weekday to London from Morpeth - a town 15 miles north of Newcastle which had lacked direct connections to the capital, as well as offering cheaper alternatives.

That’s hard to argue with, and the DfT and ORR will likely have not been too worried about the abstraction from Morpeth when it granted the licence in 2016.

But to balance the needs of providing a service for under-served areas and an OAO to generate revenue is a hard one. It’s mainly the reason why all three are attracted to routes to London using the ECML.

The four current open access proposals on the ECML are all trying to balance wants and needs, with the likes of Retford, Worksop and even Cleethorpes possible stops for both Hull Trains and Lumo. However, all those proposed paths will be using the ECML, and if approved will be abstracting further from LNER.

The counter argument to this is the track access charges that all three OAOs pay, and which LNER omitted to mention in its report.

Both franchise operators and OAOs pay them, but in different ways. Among other charges, OAOs pay an Infrastructure Cost Charge (ICC) (although currently, only Lumo qualifies for paying it), while franchise operators pay a Fixed Track Access Charge (FTAC).

FirstGroup contends that over the next two years, it will pay 10% more than LNER per train mile in fees, while on the West Coast Main Line, principal operator Avanti West Coast will pay 35% less than Lumo will on the East Coast.

Using a wider lens, the view of Great British Railways is coming further into focus - and that will mean decisions on open access needing to be made. LNER’s report demonstrates the very real threat it is experiencing from the OAOs. But that’s not the same as saying that OAOs don’t pay their way or fulfil their remits.

However, the landscape will change, and to really assess whether open access can continue in its current format, the sector needs to settle down. A pause on new access proposals would certainly give breathing space for the next few years, to allow GBR the time to really understand both sides of the argument.

If it does, then the truth in the middle may well emerge.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.