Elsewhere a diesel mechanical format was favoured and the Great Western Railway received a first unit in 1934, powered by standard AEC bus engines. The design was steadily improved and twin-engine motor coaches soon allowed 70mph running on routes such as Birmingham-Cardiff. Statistics analysed in 1950 showed that a two-car set with 124 seats had an operating costs of 11.9p per train mile, compared with steam operations with a comparable two-coach formation of 14.7p.

Initially, BR had little enthusiasm for the use of diesel power. One of the issues of the day was the need to import oil, rather than continuing to use coal produced in the UK. But after a challenge by British Transport Commission members (who today might be seen as the non-executive directors), an investigation was launched that resulted in the 1951 Harrington report.

It concluded that diesel railcars had the advantage of lower operating costs, better availability, quick turn-round, rapid acceleration and the appeal of being a modern, clean and pleasing vehicle in which to travel. It might also have added the opportunity to simplify infrastructure, which latterly has contributed significantly to the retention of many branch lines.

The first BR-designed DMUs followed the principle of lightweight construction and were introduced from 1954 using the 125hp AEC power trains originally used for the GWR rolling stock. More than 200 vehicles were constructed at Derby, before the adoption of a more far-reaching modernisation plan that required the use of other BR works and private sector manufacturers.

By the time Sector Management was introduced in 1982, these first-generation DMUs were life-expired and urgent decisions were needed about replacement. This was an era when the DfT was pressing for bus substitution on many secondary and rural routes, to which the response was the now infamous but low-cost two-axle Pacer unit. Although roundly criticised for its facilities and ride quality, it remains in service today and provides the backbone of rolling stock needs for many services with poor financial returns.

Four classes of Pacer units were delivered, reflecting the policy of procuring from a range of constructors. Vehicles were supplied by BREL at Derby (with Leyland and Alexander bus bodywork), and by Andrew Barclay (also with Alexander bus bodywork). All vehicles were 15.45m long. Introduction started in 1985 and all vehicles were powered by a 225hp engine that produced a maximum speed of 75mph.

The first of the Sprinter range of vehicles entered service in 1985. These were more conventional units with bogies and were initially built by BREL at York. Maximum speed remained at 75mph, but the Cummins power unit was up-rated to 285hp.

Two builds followed in 1988, designated Super Sprinter because they were longer 23m vehicles (compared with the earlier 19.7m length). These came from Leyland Bus and Metro-Cammell, although they also have the 285hp Cummins engine. Most of the Leyland units were subsequently rebuilt as single-car trains for use on lightly used lines.

Between 1989 and 1992, BREL at Derby built the fleet of 90mph Super Express Sprinters, with engines upgraded to 350hp and 400hp. These 22m vehicles operate over a wide range of the regional network and form the core of the ScotRail diesel-powered fleet. A sub-class of the type is allocated to South West Trains, having been converted at Rosyth Dockyard for use on services between Waterloo and Exeter.

The next series of vehicles, specified by Network SouthEast, had similar characteristics to the Networker electric units.

Described as Network Turbos, they were built by BREL at York in 1991/92, to operate Chiltern and Great Western local services in the London area at either 75mph or 90mph. The vehicles are 23.5m long, and with a width of 2.81m they require a larger loading gauge (made possible by the infrastructure characteristics of the routes, but with the drawback that they cannot be readily used elsewhere).

The Class 168 Clubman, which was the precursor of the large fleet of Class 170 units, was built by Adtranz at Derby and powered by an MTU engine rated at 422hp with a maximum speed of 100mph. They were introduced in 1998, at the same time as the production of Class 170 vehicles started, and are fully air-conditioned.

The Class 170 was designed as a train that had route availability for the national network, and was therefore narrower (at 2.69m) than the Turbos. The detailed design involved Porterbrook, which subsequently owned the fleet - with the exception of a small number of vehicles owned by Eversholt Rail.

An upgraded Class 172 design featured a 483hp MTU power unit to provide better acceleration, but the order book was curtailed after the DfT cancelled a plan to enhance the diesel unit fleet by 202 vehicles (to respond to traffic growth), given the intention to electrify a number of routes.

A great advantage of the fleet of diesel units is that they have a common coupling system, with the exception of a handful of units that have been fitted with Dellner equipment and designated as Class 171 as a result. These trains are operated by Southern, and couplers are compatible with the electric unit fleet.

With new rolling stock required by the longer-distance operators, to enhance capacity and to replace locomotive-hauled rolling stock operated by Virgin CrossCountry, two designs for a 125mph diesel-powered unit emerged.

Alstom delivered Class 180 Adelante trains in 2001 and the Class 220 Voyager series (constructed by Bombardier, mainly at Bruges in Belgium) between 2000 and 2005.

All of the 125mph units use the same engine (supplied by Cummins), with some variations in the power output at either 700hp or 750hp. There the similarities end, because Great Western specified a hydraulic transmission, whereas the Bombardier vehicles have electric traction motors.

At the same time as the Class 180 Adelante units were acquired, Great Western Holdings (which also operated the North Western franchise) ordered a small fleet of 100mph trains from Alstom. These are designated as Class 175, and have many common parts shared by the 125mph version. One unhelpful feature for train operators is that a Scharfenberg coupler is fitted - this is incompatible with the greater part of the diesel unit fleet.

Another type of unit that uses the same Cummins power pack as the 125mph vehicles is the Class 185 trans-Pennine sets built by Siemens in 2006 and owned by Eversholt Rail. The engine is rated at 750hp, with a maximum speed of 100mph.

Long-term rolling stock strategy

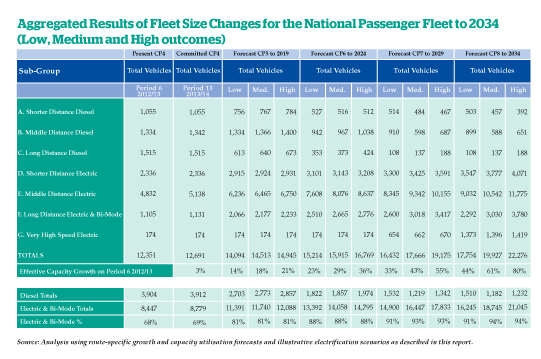

In February 2013, the results of a combined study carried out by Network Rail, the Association of Train Operating Companies, and the three leading ROSCOs and their suppliers were published. The study sought to predict the requirements for passenger rolling stock over a 30-year period to 2042, and although any forecast of this sort is likely to be wide of the mark, it is nevertheless valuable in identifying likely trends.

As a starting point, there is the assumption that the demand for services will increase, if nothing else because the population of the UK is growing and the concentration of city-based employment creates a favourable market for rail. An assessment has been made that the likely growth in passenger miles will be 2.5% per annum, with a higher figure for cities outside London than in the South East.

Electrification will have a significant impact on the type of rolling stock required. NR currently has 19,469 single-track miles open for traffic, of which 7,824 miles (40%) are electrified. A further 1,900 track miles will be wired by the end of Control Period 5, raising that figure to 50%.

Although there is no commitment by the DfT to a continuing programme, this is expected to take place. In Scotland there is a specific objective to have a rolling programme of electrifying 60 single-track miles per annum, following the completion of the Edinburgh-Glasgow Improvement Programme.

The positive benefit:cost ratio of electrifying individual sections of the network suggests that a further 2,136 track miles will justify the installation of overhead catenary in Control Period 6, a further 1,778 miles in CP7, and 1,068 miles in CP8 (which ends in 2034).

If this takes place, it will mean that 75% of the national network will be electrified and will result in vehicles equipped for electric current collection comprising more than 90% of the fleet.